The Med Diet? It’s Not Just the Food

with a Sicilian recipe for rabbit: Coniglio alla stimpirata

If you like this, please just tap the little heart up above. It gains me credibility, which is always useful.

Sunday lunch: A phrase that vies with summer afternoon--”the two most beautiful words in the English language,” said the great Henry James. Put them together and you get Sunday lunch on a summer afternoon, which conjures up sheer bliss. Then add in Mediterranean and it’s paradise: Sunday lunch on a summer afternoon anywhere in the Mediterranean, preferably outdoors.

It's a recipe for happiness, a gathering of friends, family, and strangers, all crowded around a table, sharing the bounty of good food, bright conversation, laughter (sometimes tears, in memory), little ones babbling, old folks remembering, in-betweeners serving, reaching, offering brindisi toasts, adding more to already full plates, topping up wine glasses, abundance.

In Italy it’s called the pranzo della domenica and it is ubiquitous if not quite universal. But you’ll also find it duplicated all over, in the hills above Beirut or Nice or Barcelona, along the beaches of Tunisia and Algeria, on the coast near Valencia or Bodrum, in tiny harbors on the Aegean islands.

It’s the hidden secret of the Mediterranean Diet, the one all those scientists and nutritionists and data collectors never notice and never think to mention in their analytic tomes.

The Mediterranean Diet is not just food. First of all, let’s stop calling it a diet, okay? (Although, awkward thought, that means crafting new titles for my several books on the subject.) But here’s the core problem. The thesaurus gives synonyms for the word “diet,” including: Reduce. Abstain. Watch your weight. Cut down. Cut back. And an antonym: Binge. Does that sound like punishment? Like deprivation? Like a way to lose extra pounds and regain a youthful body? All of which the Mediterranean So-called Diet is so very definitely not.

I would prefer to call it “the Mediterranean way of eating,” except that might be (you should excuse the phrase) too much of a mouthful.

Okay, so Mediterranean diet it is. And I hear you, Andrea Nguyen, with your plea that the Med diet is not the only healthful diet in the world, not by a long shot. Many, many traditional diets, all around the globe, in Southeast Asia, in Africa, in India, et al., are equally healthful and share with the Mediterranean diet an emphasis on fresh, minimally processed food, with more vegetables than meat on our plates, and complex carbs and healthy fats as good sources of energy.

What the Med diet does have, however, is decades of research and analysis, much of it based on scientific methods, to prove that diet is a major factor in healthy outcomes for all kinds of chronic diseases, from cancer to dementia to diabetes to heart disease. The result? This may be the most carefully studied major diet in the world. Not coincidentally, it may also be the one that is most misunderstood.

Misunderstood, because the Mediterranean diet is not just about food or ingredients or cooking methods. Equally important with the olive oil, the tomatoes, the greens, the beans, the pizza, the glass of wine to wash it all down, is the way food is consumed--around the table and in company with family, friends, and even the occasional stranger who might drop by. Cultural anthropologists call this socialization through food; it operates at all ages, grannies to babies, and at all social levels. A Mediterranean symbol of affluence is not a fancy car or a diamond necklace—it’s an abundant table, covered with plates and bowls of food, so much food that it doesn’t all get consumed. Even the very poor gather eagerly around a pot of beans or bread soup, a basket of roasted chestnuts, a bowl of polenta, freely sharing what’s available.

Eating is, in itself and all by itself, a social occasion throughout the broad reach of the Mediterranean, and eating together is the crux of it. You see that even with single diners in restaurants or snack bars, how they engage with the servers, with the other customers, even just a comment on the quality of the coffee that’s on offer, or the breakfast bun to go with it.

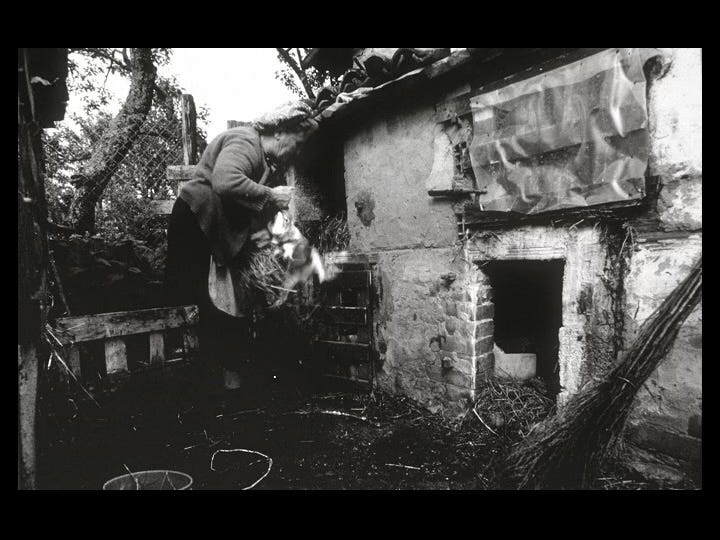

I’ve been re-reading, for the second and third time, Patrick Joyce’s Remembering Peasants, a brilliant analysis of European peasant culture in which the writer stresses the importance of home, of family, of the fireside, as the focus of that all but disappeared civilization of the peasantry. But I would argue that some of the peasant world persists, even as the economic basis of it has evaporated. It persists in habits and attitudes, and none more so than the habit of dining en famille, in a social setting, where families and friends gather regularly around the table to share food, wine, talk.

Pranzo della domenica: rarely does a Sunday go past without such a gathering in the Tuscan farmhouses that I’ve known. There the food itself is deliciously predictable—always antipasti, including house-made salumi, and crostini

piled with seasonal delights (crushed tomatoes, roasted greens, a liver pâté), followed by baked pasta al forno (lasagna to those of us from afar), vegetables from whatever grows in the garden, and meats roasted in the bread oven that’s built into the side of the house. Those meats are most often chickens and rabbits from the cortile, the farmyard right outside the door and they’re simply done, basted with oil, a splash of wine, garlic and rosemary chopped together, salt, pepper, e basta.

The recipe I offer, however (scroll down), comes from Sicily and it’s more complex, with sweet and sour flavors and the mix of capers, olives, golden raisins, and pine nuts that’s often said to indicate an Arab origin. In combination, it’s enough to convert the most determined kounelophobe/cuneliphobe. (I made it up!)

Rabbit-rabbit?

But meanwhile, what is the problem with Americans eating rabbit, meat that is recognized all over the Mediterranean as an exemplary source of protein, low in fat and cholesterol, nutrient dense, and moreover produced in a more sustainable manner than almost any other kind of meat. And it’s delicious too, with dozens, maybe even hundreds, of different ways to prepare it. But too many Americans, captivated perhaps by the Easter bunny, are upset at the thought of eating rabbit. In my little Maine town, a Thai restaurant of great renown was actually picketed by a couple of enthusiastic bunny-lovers who objected to the presence of rabbit on the menu. Can you explain to me, please why the consumption of adorable rabbits is so abhorrent when eating equally adorable lambs, another potent Easter symbol, is tolerated without problems?

Sorry but the following content and the recipe for Sicilian rabbit is only for paid subscribers.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to On the Kitchen Porch to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.