Just tap that little heart in the upper left corner, won’t you please—it gives me creds with the boss.

I have great faith in a seed. Convince me that you

have a seed there, and I am prepared to expect wonders.

--Henry David Thoreau

Winter still hovers just over the horizon here on the coast of Maine, not quite gone, always threatening to come back with another quick blast from the Arctic. Just a year ago, we were covered in fresh, blowing snow and it could happen again, the weatherman says. This has been a hard winter in the northeastern United States and not just because of the political situation. Somehow the weather seems to have collaborated with the grim state of our national affairs. Bone-deep cold, endless high winds driving the snow and sending ominous gray clouds scudding across the sky—wouldn’t you think we’d be used to that by now? But no, the winter I want is the one I remember from childhood when the ground was covered deep with snow and the skies were intensely blue and we played all day outside, building snow forts and igloos, skiing on the local hill, skating on a patch of snow-cleared ice on the river behind the house, ending the day with apple-red cheeks and near-frozen hands clasped around a cup of hot cocoa—that’s the kind of winter I keep looking for. And not finding.

Perhaps I’m just getting old and winter has lost its youthful charm.

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

But spring, inevitably, starts to push its way forward. The sun when it shines is newly warm, softening the frozen sod, searching for seeds. And the seeds in their turn begin to stir beneath the ground, to swell, to crack themselves open in their own search for life and growth. A thin root goes down, a pale leaf stretches up, and then there’s this:

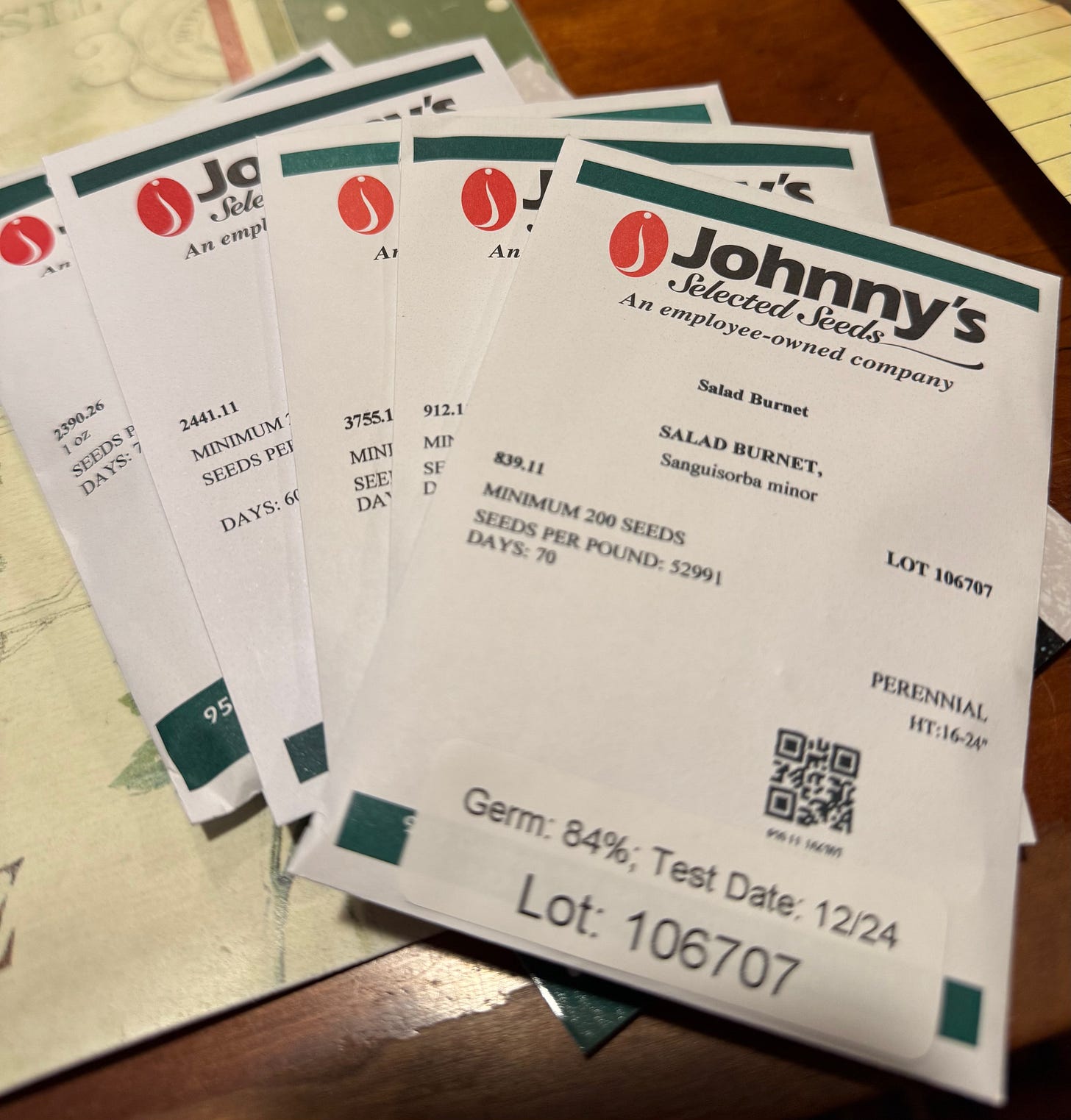

I’ve ordered my seeds from Johnny’s Selected Seeds, the great Maine supplier who dispatches seeds, bulbs, gardening equipment, tools, fertilizers, everything you need whether you’re a window-box gardener of a few parsley shoots or managing a couple hundred acres of commercial fruits and vegetables. And if you are an incipient gardener and feeling a bit timid about what’s ahead, Johnny’s maintains a terrific help line. Here’s a link to their library where you can ask a real, experienced grower for advice.

I don’t actually do anywhere near the gardening I once did when I was a lot younger and my knees were more supple. Years ago, I kept a productive garden on two separate terraces at the farm we maintained in Tuscany. I grew green beans and potatoes, onions, tomatoes (of course!), cucumbers, salad greens, carrots (oddly, I’ve never had much luck with carrots, in Italy or in Maine), chili peppers (very hard to find in Italy back then except in the south), and lots of herbs. Also, the Tuscan essential cavolo nero, better known abroad as lacinato or dinosaur kale. Late each year, just after Christmas, following the example of my neighbors, I planted fava beans and garlic to be harvested in April and May, the first fruits to come from the garden. And, to the perplexity of those same neighbors, I planted American sweet corn, both yellow and white—Silver Queen is still one of my favorite varieties.

My neighbors planted very much the same things but also masses of parsley and basil, essential culinary herbs, and many more cooking greens—chard for one, and various braising greens that were at first unfamiliar to me, like cime di rapa, which is what we call now rapini or broccoli rabe, a sort of sprouting turnipy green; crinkle-leaved Savoy cabbages; and several kinds of chicories, bitterness being a treasured flavor; also red and white speckled borlotti beans, lots of onions of course but no leeks, sweet peppers, eggplants, and lots and lots and lots of tomatoes, most of which were put up in jars as pomarola, a ready sauce for anything throughout the winter months.

All of this was the result of seeds that had been carefully saved, year after year, the previous crop giving birth to the following one, in the same way that the lievito madre, the mother yeast, from the previous baking gave birth to the risen dough for the following bake. Geneticists would have a field day probing the DNA of these innumerable seed varieties that have evolved in one place over quite possibly centuries. Just as salmon raised in the Penobscot have a distinctive DNA from the same fish from the Kennebec or Cascapedia waters, so too do fruits and vegetables develop land race characteristics, evolving over time in a single area.

There are few things in life as phenomenal, as full of wonder, as the way seeds become full-fledged plants. Tiny carrot seeds (so small some garden books advise mixing them with a handful of sand before planting), plump bean seeds, shriveled seeds of sweet corn, each contains within its unprepossessing shape the miracle of what it will become, root, stem, flower, fruit. The fat cob of corn with tight-packed milky rows, wrapped in sheath after sheath of green vegetable fiber, clinging to a tall, stout stem, reaching silky floss to a tassel of blossoms overhead—all of that is in that one miserable-looking dried-up seed of maize.

And not only is the result complex in structure, it is also packed with the elements that make further life possible, the nutrients we humans need, and other creatures do as well—mammals, worms, insects, fungi, all feeding off the results of dropping that seed deep in the ground and watering it periodically. It’s enough to make a thoughtful person believe in a grand design, a creative force that holds all this in place.

Each and every individual seed has a story to tell, but the overwhelming drama is the story of all seeds, around the world, and the struggle to preserve a unique and vital inheritance. Why unique? Why vital? Because of the genetic diversity locked up in these old varieties. As modern agriculture moves toward ever greater consolidation, and major food (and other) crops become reliant on single breeds, single varietals, single cultivars, the threat of invasive insects, fungi, or crop diseases becomes grave. It has happened in the past and it will happen again. One miserable infection can spread rapidly and infect hundreds of acres, destroying crops that are vital, economic and nutritional staples. An example is the Russian wheat aphid, one of the most damaging pests for both wheat and barley worldwide. It was found in the US in the mid-1980s and infected hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of field crops. It was stopped, according to conservation biologist Thor Hanson writing in The Guardian, only when US scientists were able to screen some 54,000 wheat and barley samples searching for strains that had a natural resistance. Breeding these strains into the existing varieties helped stop the invader in its tracks—at least until the aphid itself develops resistance.

Those 54,000 wheat and barley samples were part of the US National Plant Germplasm System, a widespread network of seed banks headquartered in Ft. Collins, Colorado, where more than 620,000 varieties (not just seeds) are kept, protected from fire, earthquake, floods, and frost. This national germplasm network is itself part of a worldwide synchrony of plant scientists working together to protect a precious resource—the seeds that humans have developed over the last ten or twelve thousand years, since the beginnings of agriculture. Most of their efforts, including what happens in the US, feeds into the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway, located far above the Arctic Circle and deep within the permafrost. This is where efforts like the US germplasm system deposit duplicates of their holdings, as a further insurance against worldwide disaster.

And now? Well, you don’t have to be a scientist or a politician or even a well-informed citizen, to deplore what has happened. DOGE, the lamentable and probably illegal US Department of Government Efficiency, has targeted the entire US gene bank network, with the usual deplorable results. You can read the unhappy details here.

All that is taking me a long way from my herb gardens where this year I plan to scatter seed for the usual parsley, basil, borage, chervil, and cilantro to go with the perennials, rosemary, sage, and thyme. But it is just more evidence of how far-reaching the Trump disasters are, whether we’re talking about saving seeds or importing European wines, cheeses, and olive oils, let alone caring for vital workers in restaurants and food service, on farms, in suburban gardens, many of whom are undocumented but nonetheless endemic and essential to our communities. The ripple effect, as it’s called, is really a phenomenal tidal wave.

The following content is for paid subscribers.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to On the Kitchen Porch to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.