Today, January 15, the health section (called “Well”) of the New York Times began a week-long series of daily e-mails about the Mediterranean Diet, complete with nutritional guidance, shopping suggestions, and recipes from The Times’s copious files (the Morgue, it’s called by old-timey newshounds). If you’re interested, you can sign up for it here.

Our purpose was to examine the growing interest in a way of eating that promised to bring better health and a better defense against chronic diseases.

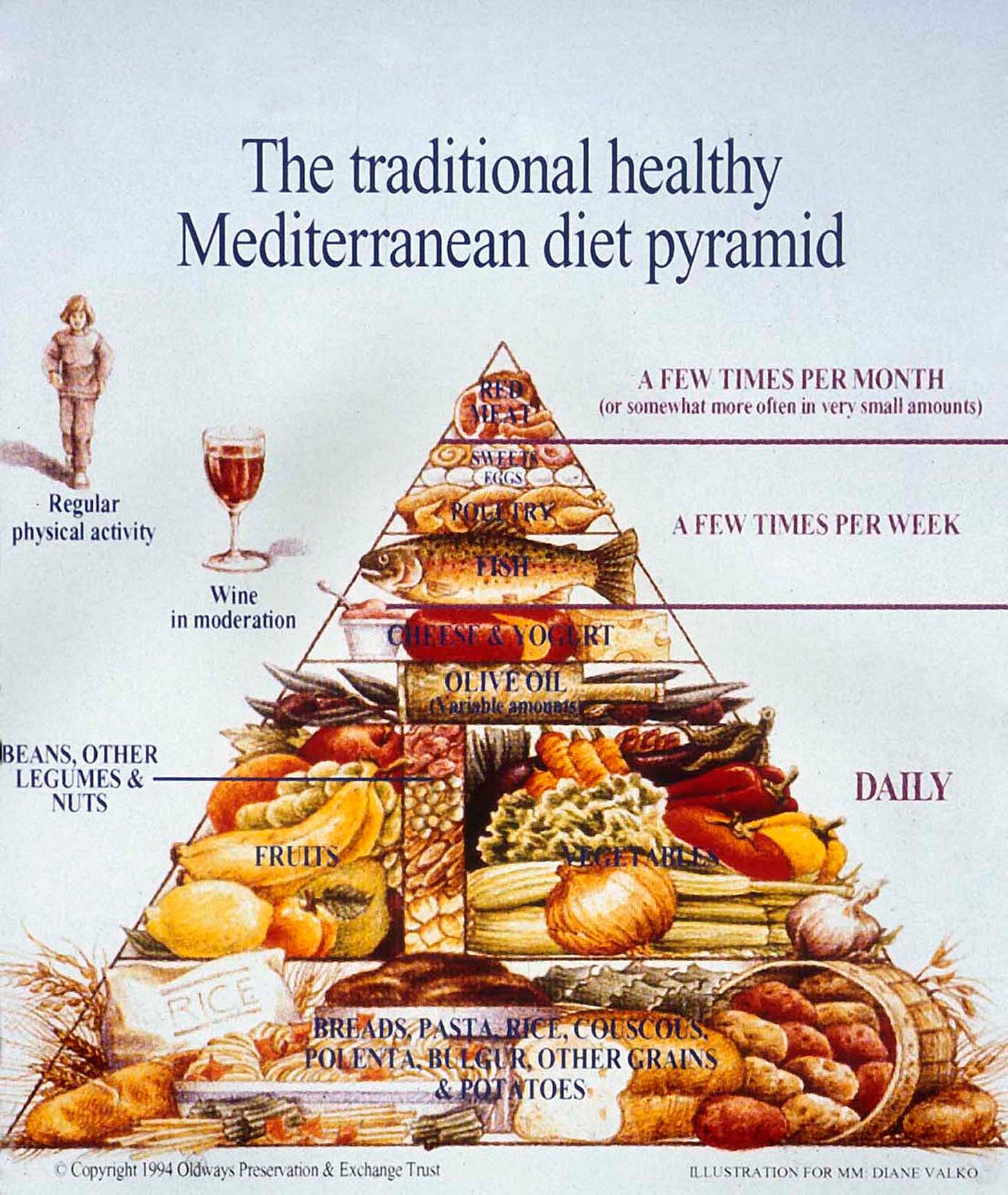

I’m very interested, in part because I was one of the original promoters of this diet, which I prefer to call a life style since diet connotes weight loss and that’s not what this is about. It was back in the early 1990s, following a conference in Boston that was sponsored by the then Harvard School of Public Health and Oldways Preservation & Exchange Trust, an organization of which I was a director, that excitement about the Mediterranean Diet began. Working together, we assembled a distinguished group of authorities, including research scientists, nutritionists, dieticians, medical specialists, cooks, chefs, food writers, and journalists from all over the world. Our purpose? To examine the growing interest in a way of eating that, unlike what was then a standard American diet, promised to bring better health and a better defense against chronic diseases, coronary heart disease and certain cancers among them.

Out of that three-day meeting grew my first cookbook, my first book about food, The Mediterranean Diet Cookbook (now available in its updated version as The New Mediterranean Diet Cookbook). I say it grew out of that conference but it also grew out of my experience over more than twenty years that I spent, for the most part, living, working, traveling, gardening, shopping, and cooking in various parts of the Mediterranean (and not incidentally raising two children at the same time).

Since the Harvard-Oldways conference and the publication of my book, more than 30 years have passed, years in which we’ve seen confirmation, over and over again, that this Mediterranean diet does indeed accomplish what we/they claimed and more—today it’s seen as protection against even more diseases and conditions that are shaped by what and how we eat, including such tough problems as Alzheimers and cognitive decline in general; diabetes, especially late-onset or diabetes 2; cancers of many kinds; and inflammatory disorders, now increasingly thought to be an over-riding or pre-condition for other diseases.

And of course, it’s a great way to eat. And to cook.

That’s not to say that there aren’t other healthful ways of eating in this vast world. Researchers have gone on to explore traditional diet patterns in Asia, in Subsaharan Africa, throughout the Middle East or Western Asia, and in the Americas, North and South. What most of them conclude is that there’s a strong argument to be made for diets based on traditional carbohydrates, whether wheat, corn, rice, or other grains, as long as they’re unrefined and untreated; on a large amount of fresh fruits and vegetables, including especially legumes; on a small consumption of meat, especially red meat, in favor of seafood and vegetable sources of protein; and--what comes as a surprise to many Americans--a very low intake of “fresh” milk, dairy being consumed, if at all, mostly in the form of fermented cheeses and yogurts.

The other piece to understand about the Mediterranean Diet is that no one would argue that everyone in the vast region of the inner sea eats like this and has always eaten like this, century after century, day after day. Food practices, including cooking habits, change from Beirut to Barcelona, from Algiers to Athens, and around all the peninsulas and bays and islands, the mountains, the great river systems, and the marshes and upland plains; historians, as well, can point to several massive changes in the ways people eat, the things they grow, the way they harvest and preserve their foods, beginning with the Neolithic agricultural revolution, a millennial-long process, and ending most recently with the invasion of fast food, industrially manufactured food (think highly processed foods), and the creation of demand for the stuff through advertising and social media—and that’s a problem right around the world.

So the Mediterranean Diet is healthy, it’s delicious, it’s easy to prepare with ingredients found in most well-stocked supermarkets, it doesn’t require special foods or cheffy techniques; moreover, the great appeal of the diet, in my view, is that you don’t have to think prescriptively. You don’t say oh, I’m gonna eat some citrus and get those valuable antioxidants. What you say is this: oh, oranges are in

season, look at these beauties in the market or the produce section, what can I do with them besides squeeze them for juice? How about a Sicilian salad with red onions? Or let’s try this orange-zested sauce with seafood? And then you get the antioxidant benefits of eating oranges but no one has to say: Eat up your antioxidants, dear!

Paid subscribers, scroll down to find recipes for these and other dishes.

On the first day of the Mediterranean Diet series, New York Times writer Alice Callahan featured whole grains, as she should. Whole grains, meaning unrefined, with all the goodness of the grain intact, are really fundamental to good health, and the Mediterranean offers quick and easy ways to add whole grains to your diet without stress or strain.

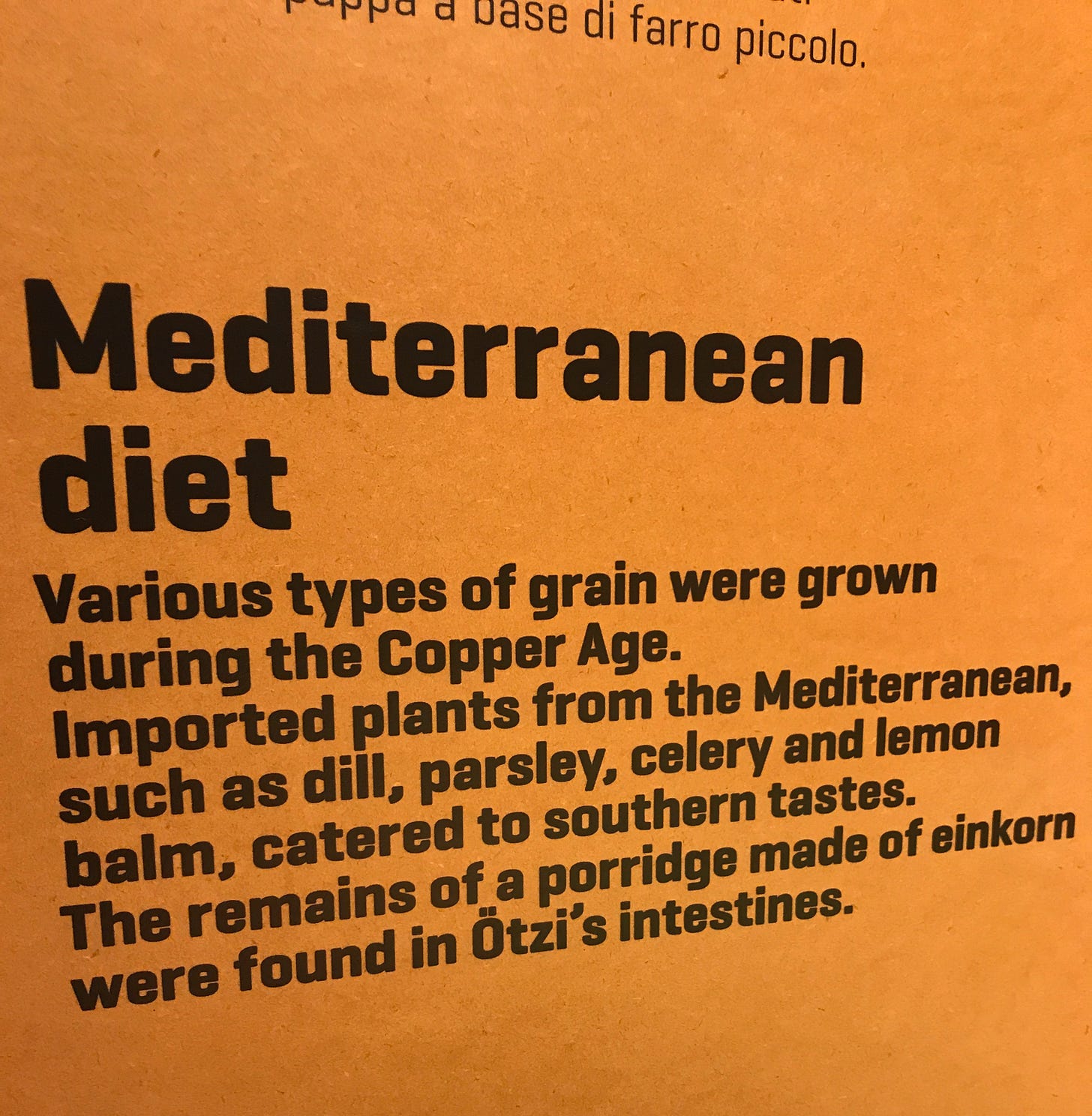

It’s an ancient tradition in the Mediterranean, going back to the earliest days of agriculture. Ötzi, the wandering hunter whose body was found in the Alps above Bolzano in northern Italy had eaten a bowl of porridge, according to the museum erected around this extraordinary discovery, made from einkorn wheat (Triticum monococcum) shortly before he succumbed. Apart from the arrow that killed him, Ötzi was in good health when he died around 5,000 years ago. Chalk it up to the Mediterranean Diet!

I’m thinking right now of bulgur (its Turkish name—it’s burghul in Arabic). This is a minimally processed whole wheat, that’s traditional in the Eastern

Mediterranean but especially in Turkey and the Levant. It’s made from hard durum wheat (T. durum) and sometimes called an heirloom grain, but it’s the process, rather than the wheat itself, that’s the heirloom. In Lebanese mountain villages it was once an annual activity involving the whole community, as freshly harvested, threshed wheat berries were boiled, then spread to dry in the sun before being milled or cracked into three grades—coarse, fine, and superfine. The result? A form of wheat that keeps well throughout the months until the next harvest, and moreover that’s quick to prepare for hungry families. (Anyone interested in traditional Lebanese preserves should take a look at Barbara Abdeni Massaad’s handsome and fascinating tome, Mouneh: Preserving Foods for the Lebanese Pantry. The gorgeous photographs will make you want to halt all warfare and make a pilgrimage to that sadly benighted country.)

But bulgur is a boon in modern pantries too. Fine bulgur is used in tabbouleh and makes a great foundation for many other salads too. All it needs is a quick soak in hot water, then drained to squeeze dry, mixed with whatever raw or cooked vegetables you have to hand, dressed with oil and lemon juice or vinegar, with maybe a dash of pomegranate syrup (aka molasses) to liven things up, and it’s ready to eat. Coarser bulgur can be cooked like a pilaf or risotto in chicken stock or vegetable broth (or plain water) and mixed with whatever the cook chooses—mushrooms, perhaps, or finely chopped meat, seasonal vegetables, or preserved tomatoes. The earthy fragrance of bulgur is a flavor base on which you can balance anything more aggressively piquant or spicy, even just onions and garlic with some fresh herbs.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to On the Kitchen Porch to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.