Tap that little heart in the upper left corner, please. It means a lot!

Last week, to honor Ukraine, I made the robust soup/stew/pottage called borsch (usually borscht in English), which has kept many a Ukrainian patriot alive and ready to man the barricades against the invading Russians over the long, difficult years of this ongoing conflict. Because, yes, don’t let anyone tell you different, Ukraine has been invaded, not once but multiple times, by the rapacious behemoth to the north. If President Trump wants to question that assertion, I would suggest he Google the word Holodomor. That’s the term for the horrifying famine, imposed on Ukraine by Russia in the early 1930s, deliberately and with malice aforethought, when millions of Ukrainians starved to death to satisfy Stalin’s greed for Ukrainian wheat. No wonder Ukraine is apprehensive of the voracious northern bear.

"In the case of the Holodomor, this was the first genocide that was methodically planned out and perpetrated by depriving the very people who were producers of food of their nourishment (for survival). What is especially horrific is that the withholding of food was used as a weapon of genocide and that it was done in a region of the world known as the ‘breadbasket of Europe’.” Prof. Andrea Graziosi, University of Naples, quoted here

Actually, the recipe I used is just one of many, many versions of borsch. Olia Hercules, the celebrated Ukrainian chef and food writer, describes all the ways this great soupy stew manifests itself, from Poland across Russia and down through the Caucasus to Iran/Persia, then all the way up to the far eastern Sakhalin Peninsula, north of Japan on the Pacific. But most folks think it all started in Ukraine.

Wherever it’s found, whatever the ingredients, however it’s put together, borsch presents a balance of rich, meaty umami with tart-sweet fruity flavors in one form or another, often with sour cherries, sour apples, green plums, prunes, or sauerkraut added. In my rendering, somewhat simplified for American kitchens, that sweet-sour savor comes from the use of apple-cider vinegar paired with sugar (or honey), but more classic versions are made with fermented beets or fermented beet “juice” called kvass, which gives it the right tang.

Nach Waxman, founder of New York’s great bookstore Kitchen Arts and Letters, may he RIP, once told me about fermenting beets in his parents’ or grandparents’ kitchen in southern New Jersey; that kitchen, he also claimed, was below the Mason-Dixon line, and he was right. I can’t tell you how to ferment beets but I can tell you that there are directions for making kvass, the fermented juice, in Darra Goldstein’s Beyond the North Wind. It takes two or three weeks so if you want to make a kvass-based borsch, plan ahead!

So how to define the thing? What is borsch and what is it not? It’s altogether an on-the-one-hand/on-the-other-hand situation, and it varies from kitchen to kitchen, throughout Ukraine and beyond, even though its origins in the Ukraine seem uncontested. Although vegetarian versions exist, borsch is usually made with a meat stock, usually beef and/or pork, with plenty of bones to give the stock its unctuous heft. Basically, it’s beet soup, although there are examples of borsch made with greens, especially the sour sorrel soup beloved of Eastern European Jews, called schav or tshav. And if I tell you that it’s a cold-weather soup, made of wintertime root vegetables—the beets, yes, but often also with potatoes, carrots, turnips, parsnips, and other rooty things added—then I must add that there are delicious summertime versions, too, often served chilled. Like that schav. Or like Polish chłodnik, a light, clear, deep-rose liquid, properly tart and sweet, served garnished with chopped hard-cooked eggs and dollops of sour cream. On midsummer nights in the Polish countryside, this is elegant party food, taken in the freshness of the garden when the peonies are in fragrant blossom and a twilight glow persists for long hours after a late sunset.

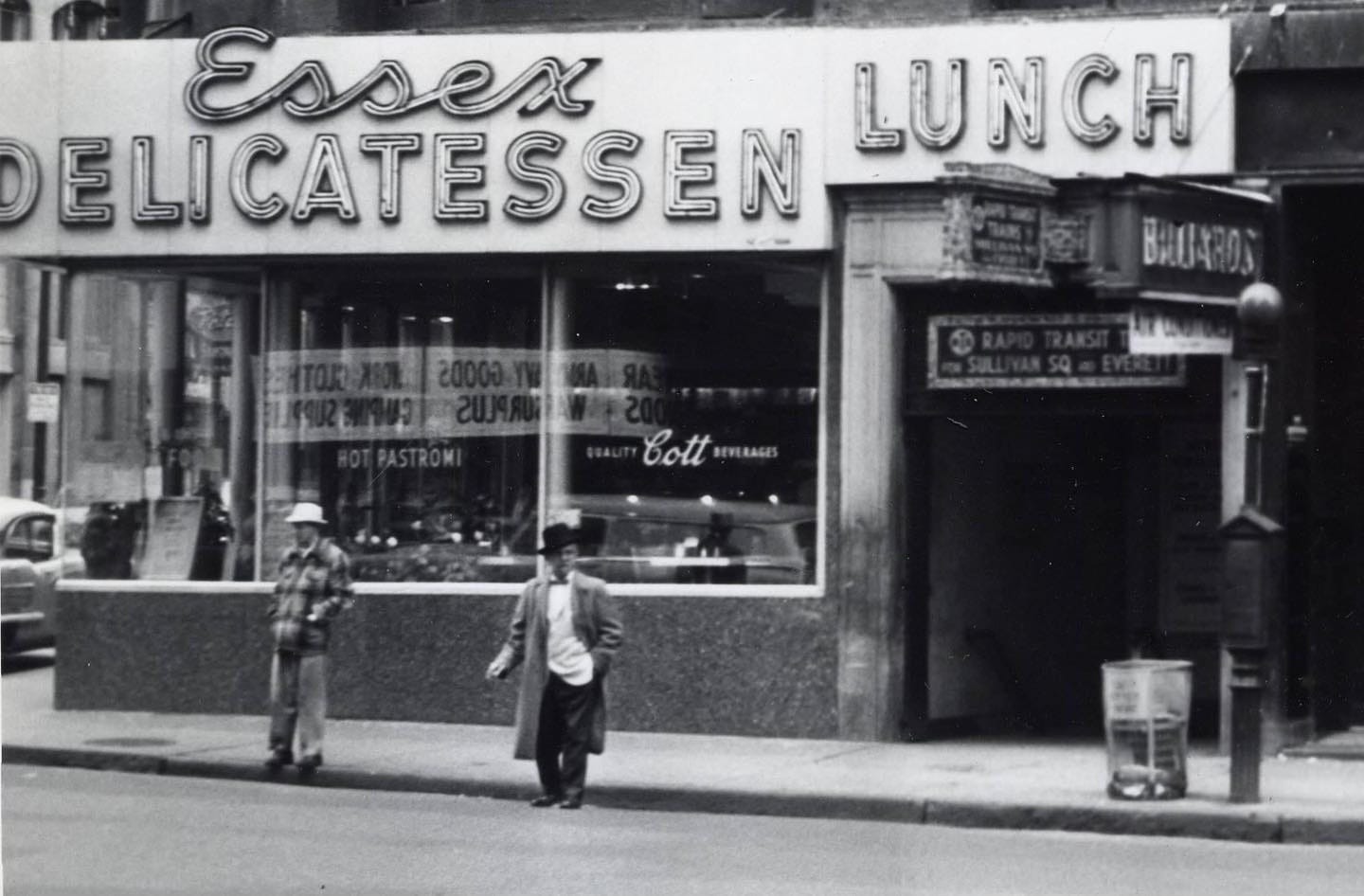

So which is it, borsch or borscht? My hours of research seem to confirm that it is or was originally borsch, but became borscht, with the final T, in Yiddish, for linguistic reasons that escape me. And in Yiddish, it got carried to the United States by Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, for whom it was a heimische memory of the home kitchen. That’s how it became borscht in American English. And that was what I had in the old Essex Delicatessen on Washington Street in Downtown Boston when I was about 12 years old and my father ordered it for me. It came with a whole steamed potato on the side, a hot potato to dip in the fragrant stew. Plus a big bowl of dill pickles to go with it. Unforgettable!

Borsch or borscht, it’s a dish that has to be made in quantity so it’s perfect for that Sunday lunch you might be planning for eight or ten guests. You could even do something creative and charge your guests, say, $20 or $25 each, then send the collection to World Central Kitchen, the remarkably effective organization headed by Chef Jose Andres that feeds struggling people all over the world, from Ukraine to Gaza to wherever there is need. Mark your contribution for use in Ukraine.

Borsch is not exactly complicated but it does take time to produce, although that time can be spread over several days, making the cook’s job a lot easier. Much of that time is spent just letting the stock cook gently on top of the stove or cool down in the refrigerator. If you make the rich stock and boil the beets ahead of time, then all you have to do is combine everything on the day you plan to serve it.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to On the Kitchen Porch to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.