Please do me a favor and tap that little heart in the upper left corner. And if you really like my kitchen porch stories, sign up as a free or paid subscriber.

I have been twice to Bethlehem, the first time out of curiosity, the second time for food. Both times were captivating although the experiences were very different. The first was long ago in the early 1970’s during the period of the Rogers Peace Plan, a project spearheaded by U.S. Secretary of State William Rogers to promote Israeli withdrawal from Palestinian territories occupied during the 1967 Six-Day War. Back then it sometimes seemed as if a one-state solution, uniting Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs under one government, might be possible. In the event, it was neither the first nor the last misguided (and failed) effort to bring about peace in the Middle East.

a visit to the site of the birthplace of Jesus seemed appropriate

My then husband, who worked for a U.S. news magazine, was headed off to investigate the status quo in the occupied territories, and I went along, from Beirut to Damascus to Amman, then down across the Jordan and over the Allenby Bridge, up to Jerusalem. Christmas was but a week away and Bethlehem was close by. In those distant days people easily traveled back and forth between the two, so a visit to the site of the birthplace of Jesus seemed appropriate. I do not recall much of that trip except that in the ancient Church of the Nativity (said to be the oldest continuous house of worship in all of Christendom), I stumbled on an Armenian Apostolic service in the crypt of the basilica. Was that the grotto where Mary wrapped the infant in swaddling clothes and lay him in a manger? I couldn’t be sure in the dim candlelight. A multitude of flames flickered through thick clouds of incense while bearded men in dark gilded robes, bowed and chanted rhythmically, their muttered voices echoing beneath the arches. The mysteries of early Christianity hovered in the smoky air. I am not a Christian, not really religious, but at the moment I was enchanted, almost ready to believe.

Later, in a Jerusalem souq, I bought a traditional Palestinian dress or thobe, made of heavy, hand-woven silk, embroidered with elaborate patterns of the tiniest stitches imaginable, many of them also done in gold thread. The design of these thobes, the shopkeeper told me, were particular to each region of the country. As it happened, the one I chose came from Bethlehem. I treasure that dress to this day and I pray the woman who gave it up received a commensurate sum.

Fast forward to 2010 and my second trip to Bethlehem, on assignment from the old Saveur magazine. I had proposed a story about Palestinian food focused on the olive harvest, to which the editor’s response was predictably lackluster. But then she called me back with exciting news: the Israeli tourist promotion board was funding a food-and-wine tour for journalists. Would I be willing and could I combine it with my Palestinian story? I swallowed hard, crossed my fingers behind my back, and said yes, of course. I did not have the heart to point out that the last thing in the world the Israeli tourist board wanted to promote was Palestinian cuisine.

And so I embarked on a very strange tour, during which I was taken to many excellent restaurants and abundant markets in Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, and elsewhere, stayed in rustic but comfortable country resorts as well as the super-posh King David Hotel, tasted wine in a giant Galilee cooperative whose manager assured our small group of American writers that our President was a not-so-secret Moslem, learned the complex rituals of kosher wine-making, visited with the great baker Erez Komarovsky at his farm on the Lebanon border, and listened to our earnest guide repeat daily, if not hourly, that the Land Of Israel, which she capitalized vocally even to the preposition in the middle, was eternally and forever the home of the Jews.

and then it was Bethlehem and the nearby village of Beit Sahour

And then I was free to pursue my real interest, in Bethlehem and the nearby village of Beit Sahour, which lies on a ridgeline just east of the holy site. Above it loom the high-rise blocks of Har Homa, a huge Israeli settlement that has been highly contested since its establishment in 1991. Los Angeles imported to the Judaean desert, I thought.

Pause for a brief history lesson: Palestine’s territory once stretched from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean, a region noted for abundant agriculture, whether rain-fed or irrigated. If you remember grade-school history, you know that this was the western tip of the Fertile Crescent, an ancient birthplace of agriculture. Not surprisingly, throughout the millennia, it has also been a region of conflict and struggle, coming under empires from the Assyrians to the Romans, finally being ruled by the Ottoman Turks until the British pushed them out in World War I. When the British Mandate ended in 1948, the land was carved into an approximation of what we know today as Palestine and Israel; I need hardly add that the boundaries continue to be in hot dispute. The resulting conflict has raged for the past half century, often involving far more of the world than simply Israel and Palestine, and far too often, as today, entailing guns, bombs, stones, and other weapons of destruction that have failed monumentally to resolve the situation.

But I was in a different zone in Fairouz Shemali’s immaculate, sun-lit kitchen in Beit Sahour, where she showed me over several days why she was said to be the finest home cook in all of Bethlehem. Among the many dishes we crafted together, what stand out are sfiha, a Palestinian version of the flatbread that’s ubiquitous throughout the Eastern Mediterranean, crisp-crusted and topped, like pizza, with a delectably spicy, savory mix of meat and vegetables; and maqlouba, a rich combination of lamb, eggplant, cauliflower, and rice, cooked in a deep pot that’s inverted onto a platter for presentation (that’s what maqlouba means—overturned). A high-school history teacher, Fairouz was also a fine cooking instructor, though she quickly became exasperated with my hapless efforts to shape those flatbreads without the edges cracking. (I will add her recipes in another post, for subscribers only.)

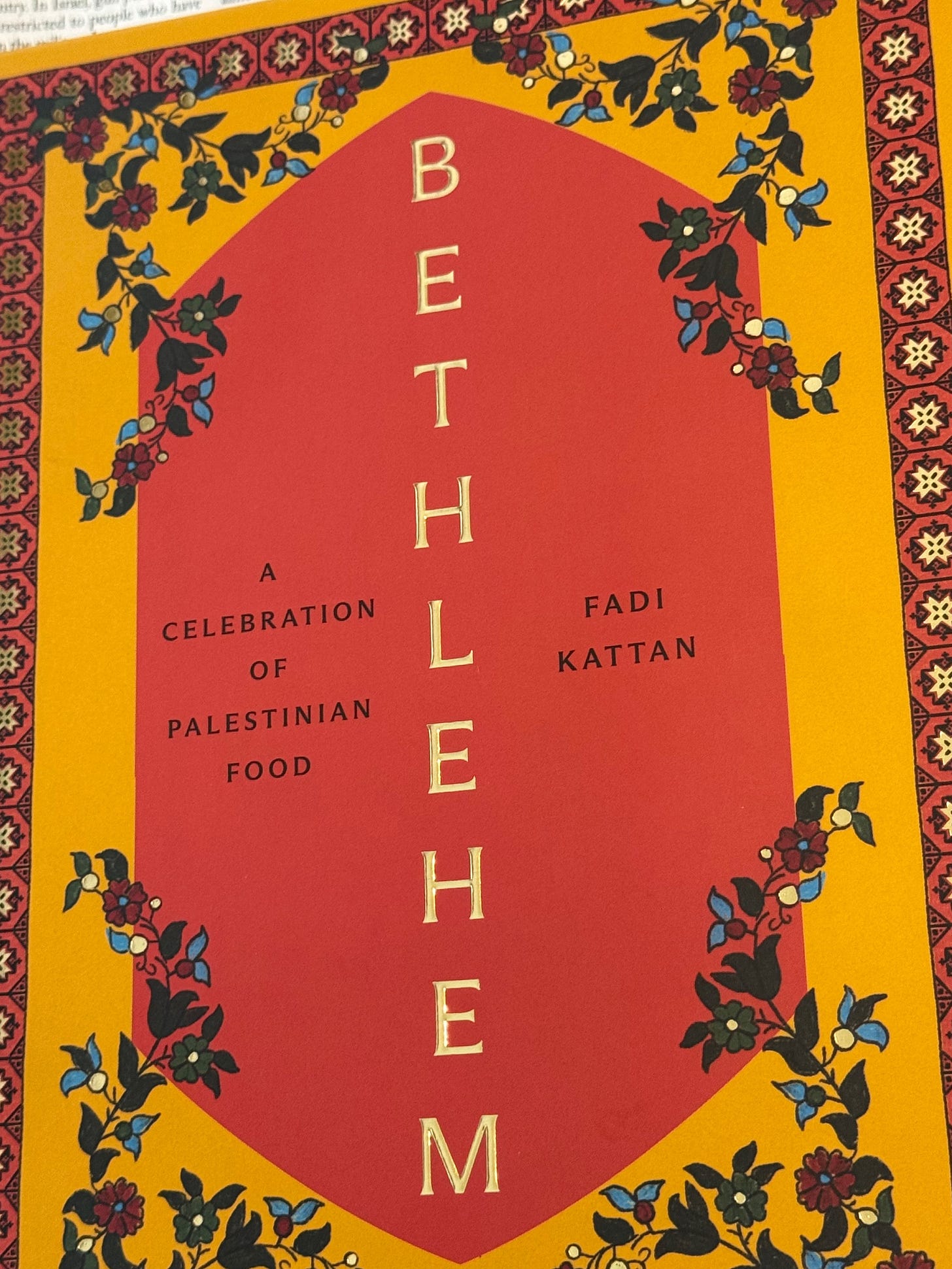

What brought all this back to me was not just the unhappiness of the current conflict in Gaza, about which I’ve written in the past, but the arrival of a new book with the very evocative title: Bethlehem (Hardie Grant Publishing). This is Chef Fadi Kattan’s celebration of his beloved family home and the foods and dishes that take him back there. I had not known the chef before seeing his book but now I have his two restaurants, Fawda in Bethlehem and Akub in London, on the top of my list for next time I’m in either of those places.

Why? Because this is food, this is a book, that absolutely rings with authenticity, a kind of truthfulness that a reader senses is heartfelt, even as that same reader is hard pressed to define the words. Not just a collection of recipes (although that too is important), this is a memoir, a memory trip through the souqs, the gardens, the kitchens, the bakeries and markets, the tables and dining rooms of Bethlehem as it was in the author’s youth—not so long ago but a very different world from the one we know today through our television and news reports.

Kattan doesn’t shy away from that difference either. Talking about the Dead Sea, for instance, he recalls long ago family vacations to water-rich Jericho nearby and what it’s like for Palestinians today, with the Bedouin population forced out and the once abundant water diverted to Israeli settlements. As for the famous Dead Sea salt, with its “sharp, pure, unpolluted” flavors, that is almost extinct. (One reason it’s so pure, I learned, is because there is no life possible in the “dead”sea, hence no source of pollution.) Only one Palestinian producer remains. It is virtually impossible to get Israeli planning permission for another establishment. Indeed, the waters of the Dead Sea are severely diminished, dropping at the rate of three feet annually, in what Kattan doesn’t hesitate to name “a shocking environmental disaster.”

But much of his account is taken up with happier days when the Kattan family were prominent in the international textile trade, going back to when Palestinian cotton (“kattan” in Arabic) was exported around the world. Chef Fadi writes about his parents and grandparents, calling up a world that has all but disappeared except in memory. And what precious memories these are: Baba Fuad, his father, rising early and preparing breakfast for the entire family to enjoy together; the fragrance of breads warm from the bakeries of Bethlehem, including the legendary taboun bread, baked on hot stones that leave a pebbled surface, perfect to trap fresh yogurt for a quick snack; the humble lentil soup made by his sophisticated and well-traveled mother Micheline; or the fragrance and flavor of fresh olive oil from Sebastia, “a tiny hilltop village in the northern West Bank.”

The photos alone, of people, places, ingredients, evoke that world in all its beauty and give a sense of haunting loss.

As for the recipes, many of the ingredients Chef Fadi calls for have become familiar recently, at least to North American consumers—grains like smoky fareekh and bulgur/burghul, or rich tahini (which he calls tahinia, possibly closer to an Arabic pronunciation). Others, like grape dibs or molasses, or white jibneh beida or jibneh nabulsi (a similar brined cheese made in Nablus), or hwerneh, very sharp-tasting mustard greens to be lightly fermented in yogurt, or green (unripe) almonds for pickling, may be hard to find. But often substitutions are not lacking and there is such a variety from which to choose that a curious cook will not be disappointed.

Below the paywall, you will find Fadi Kattan’s recipes for green shatta, the very spicy Palestinian all-purpose dip, to go with vegetables, braised chicken, grilled fish, whatever suits.

And Chef Kattan’s recipe for Palestinian watermelon salad, which is a little different from the watermelon salads you may be used to. It also comes with a story: “Watermelon became highly symbolic. . . when, after the occupation of the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza in 1967, Israel made it illegal to carry the Palestinian flag. In the early 1980s, Palestinian artist Sliman Mansour circumvented this ban by painting the watermelon, its colors being the same as those of the flag.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to On the Kitchen Porch to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.