Please give that little heart in the upper left corner a tap to say you like this.

This is a repost of an article I wrote more than two years ago. I’m redoing it now for obvious reasons. What is happening to Lebanon and the Lebanese is unconscionable. No, it’s not worse than what is happening in Gaza—few things are. But it’s happening in a place I’ve lived, worked, shopped, cooked, raised a family, and loved the people and the culture. Read on, please!

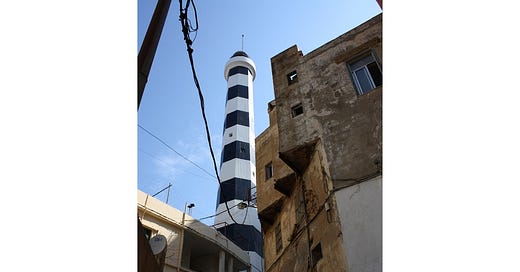

I left Beirut with my two small children in tow in June of 1973 after three years in the growing turmoil of a city that would not admit to being at war. Three years earlier, the chaos of Lebanon had seemed supportable, a bit dangerous perhaps but only for those who got in its way. We had a bright and spacious flat by the manara, the lighthouse. On an evening early on, when I was enjoying an after-dinner coffee with the children’s father on our terrace overlooking the Mediterranean, I remarked on the fireworks I could hear exploding all over town. There had been elections that day in the Lebanese Parliament, and the winning party was celebrating. “How delightful,” I said.

“Those are not fire-works,” said my husband, who had experienced revolution as a child in Bolivia, “those are fire-arms. We will now go inside and close all the shutters.” Which we did.

But life was not always so dramatic. There were long, sweet times, evenings with friends around tables laden with unimaginably delicious foods and wines, opulent receptions in high-ceilinged marble halls dating back to the Ottoman Empire, simple picnics in the mountains, treks to ancient ruins (“ah, it’s only Roman,” we said, tossing back pottery sherds picked up along a cobble beach), skiing the slopes at Faraya and the Cedars then lunching the same day al fresco at a seaside tavern, talking and listening, arguing, discoursing, everything from politics to art to history to idle gossip, and learning so much about a part of the world that was utterly unfamiliar to me at first but that I came to love with a passion.

Every other day I shopped in the Souk al-Franj, the historic fruit and flower markets of downtown Beirut. I’d carry salad greens home for lunch (fatttoush or tabbouli), then have provender for the next two days delivered to my door that afternoon in tall woven baskets that were emptied on the kitchen counters. The fish was almost live, so fresh, from the Mediterranean, the meats were local, mostly lamb and chicken, the flatbreads were often still warm, the wine came from historic French vineyards in the Bekaa valley, and the cheeses? Well, I didn’t pay much attention to the cheeses but the yogurt was tangy and thick. I often felt like the hostess of an unofficial club for visiting journalists, academics, politicians, never knowing quite how many might be at the table for lunch or dinner. Hospitality, I learned, is the key to Arab culture, no matter where you are. We lived in an abundance that was staggering at times, far from the refugee camps on the outskirts of town where second and third generations were living, stateless since 1948 and often in unrelieved poverty.

I did not leave Beirut with regrets, however. The children’s father had decamped to Asia months earlier, sent to run the Hongkong bureau of the news magazine that employed him. I stayed on in Beirut, hoping to finish preliminary work for a doctorate in ancient history at the American University (AUB), still incomplete to this day. But the Palestinians, in the refugee camps and outside, were stirring, skirmishes and street fighting increased, and by April of that year, the children’s schools had closed. I came home from the AUB library one lunchtime to find my seven-year-old leaning over the balcony of our flat: “Mummy,” she called down to me, “I don’t want to go back to school this afternoon.”

“That’s fine, dear,” I said, “but why?”

“Because the bus driver made us all get down on the floor of the bus so people wouldn’t shoot us.”

So okay, my darling, you don’t have to go back to school.

And she did not. From that moment on.

After that it got worse for a while.

Together with two friends, I escaped to a house we had rented on the north coast of Cyprus and that was a lark, three mothers, seven children, and one de facto uncle, a friend who had broken his ankle and huddled in the garden like an ancient Brit, calling out for more wine, more tea, and please send someone down to Kyrenia to get today’s Herald Tribune. When we went back to Beirut it was calmer but very clearly not a place to live, as I had intended, as the sole resident parent of two very small children.

And so we left. We took a boat from Beirut to Venice, a cruise ship actually, with an Italian crew and a German passenger list except for ourselves and one other American family, missionaries on their way home from somewhere in East Africa. The Germans had costume balls every night, with paper costumes supplied by the cruise line. Overweight German men sweated in paper hula skirts with paper leis around their sloping shoulders, twitching as they danced to the music of the ship’s orchestra. But the Italians in the dining room were agreeable and, like all Italians, doted on the children. “Where are you going?” they asked. “To Teverina,” I said. “Ah, Teverina! Che bella!” But of course they were all from south of Naples and had no idea what I was talking about, a tiny hamlet in the hills between Tuscany and Umbria where we were headed for the summer.

After Beirut, the ship called at various ports where the passengers got off and squeezed into vans that took us to the local sights. And thus I was able to touch down on many places I had been studying intently, the Minoan ruins at Knossos on the island of Crete; Agamemnon’s kingdom, Mycenae rich in gold; and finally dazzling Dubrovnik sparkling on its hillside, a fitting prolegomena to Venice herself.

But I missed Beirut and I have missed it ever since. When people ask where, of all the places I’ve lived in the world, I most want to go back, I always answer, “To Beirut. In 1972.” To a world that has disappeared.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to On the Kitchen Porch to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.