I live in a coastal Maine community with a vigorous recycling system. Years ago, when I first moved back to my home town, I was offered a chance to sign up for regular weekly trash pick-ups. It’s a private service with an ancient heritage, going back to Alice Yates, a notably stout woman, who was the garbage collector when I was growing up. Wayne Heal is her successor, though there have been several others in between. Customers pay for the service, though I’m not sure how much because in the end, I didn’t enroll.

As an avid environmentalist, I preferred to handle my own garbage, and that way to keep a close watch on what I consume and what I waste. So, I make regular trips to the local dump, more politely known as the transfer station (no one actually calls it that). There I’m faced with separate, very large dumpsters, containers for various kinds of plastic (including one perplexingly labeled “Natural Plastic”), cardboard, boxboard, newspapers & magazines, glass, cans, and returnable bottles. There’s also a bin for no longer used eyeglasses, another for clothing, and one for compostable materials (true garbage), as well as a swap shop where anything deemed re-usable can be left for another, perhaps more adventurous consumer—books, dishes, cookware, books, gardening tools, chairs, old window and door frames, and yet more books. (We are a literate community with not one but two substantial public libraries situated just a mile apart.)

The dump is a place like the post office where you run into people you haven’t seen in a while, people you like but somehow never seem to get together with, and you exchange information about the weather, of course, and family doings, any coming holidays, where you’ve been and where you’re going, how bad the traffic is on Route One, what’s happening in the garden (“damned wild turkeys dug up all my garlic--I had to replant the whole lot”). These days we stay away from politics, even something as apparently inconsequential as whether or not to finally install parking meters downtown.

In addition to the dump, where I recycle newspapers, magazines, trash from mail-order purchases (always an inordinate amount of plastic though it has diminished slightly from a few years ago), and wine bottles, I also compost, with the help of a local business called Scrap Dogs run by Tessa and Davis, a dynamic and hard-working couple. Every week they send someone around to my front doorstep to pick up a bucket of compostables from the kitchen.

This little exercise in civic responsibility leads me to lots of cogitation on the subject of food waste, which is very much in the news these days. Just last week an invitation arrived from the Oxford Food Symposium to join an online group talking about ways to mitigate waste in the kitchen and improve access to food for those without. Among the suggestions were: saving heel-ends of bread in the freezer, then using them to bulk up soups; saving parmigiano rinds to add umami to those same soups; using steak and chicken bones for stock; making Mexican tepache by steeping pineapple parings; substituting carrot tops for parsley; infusing the green tops of strawberries in vodka to make. . . I’m not sure what exactly. With the exception of the vodka, and possibly of the very bitter carrot tops, these strike me as things smart cooks and thrifty kitchen mavens have always done, nothing new there, as long as you have adequate freezer space for all those bread ends and vegetable scraps and bones and remember to label and date each little plastic bag.

But for many people in the world, adequate freezer space is a grand, even quite probably nonexistent luxury. In fact, for most people in the world, food waste is not the problem it is in the US, the UK, and a few other parts of the developed world. The problem, in fact, is food acquisition. And how my salvaging of bread ends and cheese rinds is going to solve that problem continues to be a mystery.

I don’t mean to suggest that food waste is not a dilemma. It is indeed and a startling one—a growing one too, as is evident from online statistics: the 96 billion pounds of food wasted annually in the US in 1995 had grown to 108 billion pounds by 2023. Each year, we Americans lose more than a third of our food supply. And meanwhile there are at least 38 million people in the United States alone who are in what statisticians call food insecurity, meaning they don’t know if they will have supper tonight or not. In Maine, my state, as was reported earlier this year, food insecurity hits the very young especially hard. Go into any elementary school classroom in the state and count the students—out of every seven, one small child will go to bed hungry. This is intolerable.

“Think of the starving Armenians,” my father would say, as he urged us to clean our plates, echoing a meme that was once recited to him by his own mother. And what, I eventually asked, would starving people do with that nasty bit of mashed squash that I couldn’t quite bring myself to swallow? If I freeze parmigiano rinds for an eventual soup, is that going to make more parmigiano rinds available for the hungry of the earth?

Is this really the way to deal with food waste?

There’s another quandary related to food waste and that’s its environmental consequences. The number one material crowding US landfills (another polite word for garbage tips), the single most prominent feature of our dumps, is discarded food. You might be surprised—I certainly was—to discover that anaerobic digestion of all that food produces both methane and CO2, as well as other greenhouse gases. Of the world’s total emissions each year, a full 6% comes just from the food we discard in landfills. Think of that the next time you start up your smart electric vehicle.

In the rural Tuscan village that I called home for many years, food waste was not a dilemma. First of all, because just about everything edible was in fact eaten, a reflection of a time in the memory of my neighbors when food was in short supply and every bit counted, including the chestnuts that were dried, ground to a flour, and made into a sort of bread. Anything left over from the family table went to feed the animals—the pigs, the chickens, the ducks, as well as the dog and the many cats. Quite simply, nothing truly was left over, meaning there was no waste.

Think about how Tuscan cooks use bread, for instance: Bread on the farm was baked every ten days or so in the outdoor oven and kept in a big wooden chest in the kitchen where it slowly evolved into what they call pane raffermo. And this “firmed-up” bread has multiple uses, even when it’s almost rock hard. Soaked in bean broth, it becomes the foundation for zuppa di fagioli or ribollita, two classic Tuscan hearty soups; soaked in tomato juice and vinegar, it becomes panzanella, a refreshing summer salad; dipped in hot broth and then dressed with an elaborate mash of chicken livers and veal spleen, it becomes crostini neri, the antipasto to proceed any celebratory meal; cooked and mashed with pelati, garden tomatoes preserved for the pantry, it becomes pappa al pomodoro, beloved by small children as well as nostalgic adults. There may have been other uses too, but those are the ones I know—and the point is, nothing of that bread was ever wasted. If it got just too hard to deal with, it went to the chickens who pecked at it until it was gone.

Of course, most Americans no longer live on a farm; most Americans no longer bake bread or even cook their own meals, preferring to eat carry-out, microwave prepared meals, or pick up something at the local drive-thru for dinner. And of course, most Americans don’t have pigs or chickens or even a compost bin to take all those discards.

A report for the Natural Resources Defense Council back in 2017 indicated that in the United States, a full 40% of our food supply is simply wasted. But where are the culprits? Most similar reports target households for the great quantities of uneaten food that gets tossed for all sorts of reasons. Overbuying is one, not correctly estimating how much salad your household will consume before the lettuce goes limp and the cucumbers sag. Another is overcooking—again, not judging how much of that salad your family will actually eat and tossing the soggy remains from the salad bowl into the garbage. (Well, you could compost them, as you could that limp lettuce, but unless you have a garden or live in a community like mine with a regular pick-up of compostables, you’ll soon run out of space. And patience.)

But we also waste food in other ways—production on the farm is one, where farmers regularly and deliberately over produce so that, if there’s a crop failure, they might not lose it all. Then too a lot of food gets spoiled in transit—lettuce or strawberries or celery from California fields may get overheated or delayed en route to the east coast and break down to the point it’s no longer edible. Often a whole truckload of produce may be turned down at its destination for some glitch in the packaging. And then there’s the enormous amount of our food supply (97% of our seafood!) that’s imported, often from very distant parts of the world and anything can and does go wrong along the way. The globalization of the food chain means every single step in the long string is fragile. Finally (but it’s not final, just an end step), consumers may very well turn their collective nose up at somewhat imperfect fruits or vegetables, apples with a blemish, tomatoes that are judged too soft. You get the picture.

So although home kitchen managers, meaning the person in the household who buys and prepares the family’s food, get a large part of the blame, it’s a little like blaming home consumers for the overweening problem presented by plastics. Yes, consumers can and should do their part to solve the problem, but the problem will not be solved by consumers alone—it will take a major shift in the worldwide supply chain to effect true change, whether of plastics or of food waste. And that will come about only through government intervention, at the national and the international level.

Don’t hold your breath!

In Search of a French Apple Cake

I’ve been reading about a very buttery apple cake that is usually referred to as “French Apple Cake,” or “French Butter Apple Cake.” At least, that’s the reference in English—and English is the language in which I’ve found almost all of the references. Most (but not all) of them credit the recipe back to Dorie Greenspan and her fine compendium, Around My Kitchen Table, for what she herself calls “Marie-Hélène’s Apple Cake.”

I happily made the Dorie cake—scroll down for a recipe for my interpretation—and it is indeed delicious, especially with the right kind of apple.

In a local farmers market, I stumbled on a late harvest of tart Northern Spies, no longer a familiar apple to many cooks, but praised for their virtues for both cooking and eating out of hand. It was perfect for the French butter apple cake.

Still, I continued my search for a French version of the recipe and came across this curiosity in Elizabeth David’s French Country Cooking:

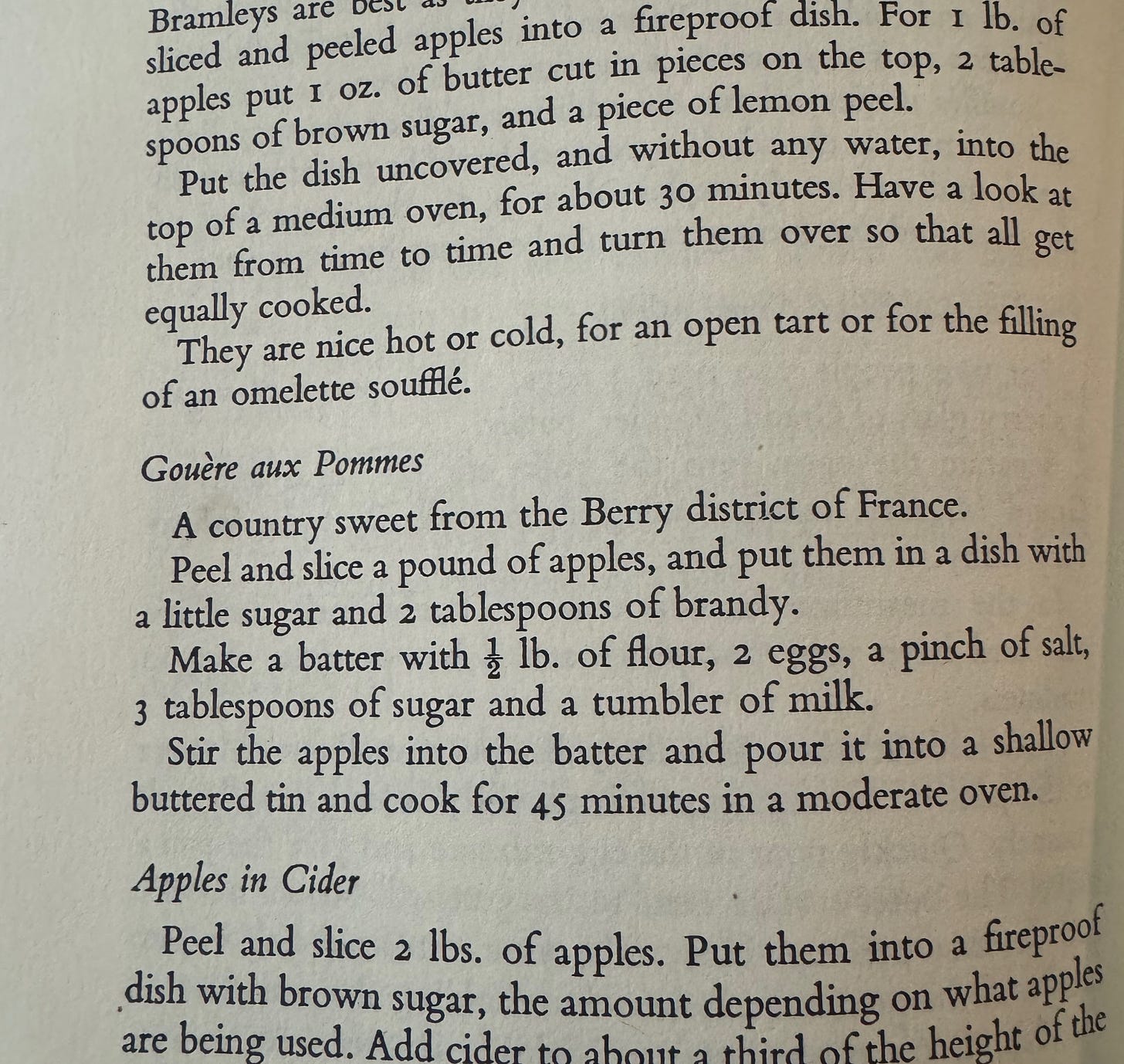

Called la gouère, it was described by Mrs. David as “A country sweet from the Berry district,” as in “Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry.” This is her recipe:

But, you will note, no butter!

As it happened, my near/dear neighbors, Mary and Dave, were traveling in the Berry at that very moment, ecstatic about all the architectural treasures they found there, including the great cathedral of Bourges. “Quick!” I messaged them, “find me a recipe en français for la gouère.” They did, bless them, and here it is:

From La cuisine berrichonne de Hugues Lapaire:

Pour obtenir ce gâteau : Émincez des pommes (une livre) très fin. Faites les macérer dans du cognac (deux cuillerées à bouche) et du sucre en poudre.D’autre part, délayez dans une terrine de la farine (une demi livre), deux œufs, du sel (une pincée), du sucre en poudre (trois cuillerées), et du lait (un verre). Lorsque votre pâte est liquide, mélangez-y vos quartiers de pommes, graissez une tôle à rebords, mettez votre pâte à gouéron et laissez cuire au four trois quart d’heure. Mais, où est le beurre? Where’s the butter?

Nonetheless, I actually made this and it was okay but flat, like a thick pancake, and nowhere near as rich, tasty, and light as what I now call the Dorie version, even though I added baking powder to leaven it a bit. Obviously, the butter was key. Digging even deeper, I discovered that a variation on this seems to exist in country districts all over Europe. I found a Russian version, from Olga Massov in The Washington Post, that came from the restrictive Soviet years hence lacked butter but was otherwise almost a duplicate of the Dorie one. A British version has a lot of butter and a lot of sugar, including Demerara sugar sprinkled on top to give it crunch—not a bad idea actually. And the Italian version, almost predictably, has pine nuts (pignoli) scattered through it, another good idea. There are very similar apple cakes from Ireland and from Syria, there’s even a Czech cake, and a classic German one.

So what to make of all this? Not much, except to say that in the fullness of apple season, which is right now, when the best apple is the one you bite into straight off the tree, the second best is blended with butter, sugar, cinnamon, vanilla, wrapped in a cake-y, pie-y, torte-y confection and taken best of all warm from the oven with a dainty dollop of whipped cream or ice cream or even plain yogurt.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to On the Kitchen Porch to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.